A New American Food Pyramid and What St. Hildegard of Bingen Would Say About It

For the first time in decades, the United States has quietly taken a step back toward reality. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030 abandon much of the ideological confusion of the past and return to a principle so simple it feels almost revolutionary: human beings thrive on real food. Food that is minimally processed, naturally nutrient-dense, and recognizably derived from plants and animals, rather than from laboratories and factories.

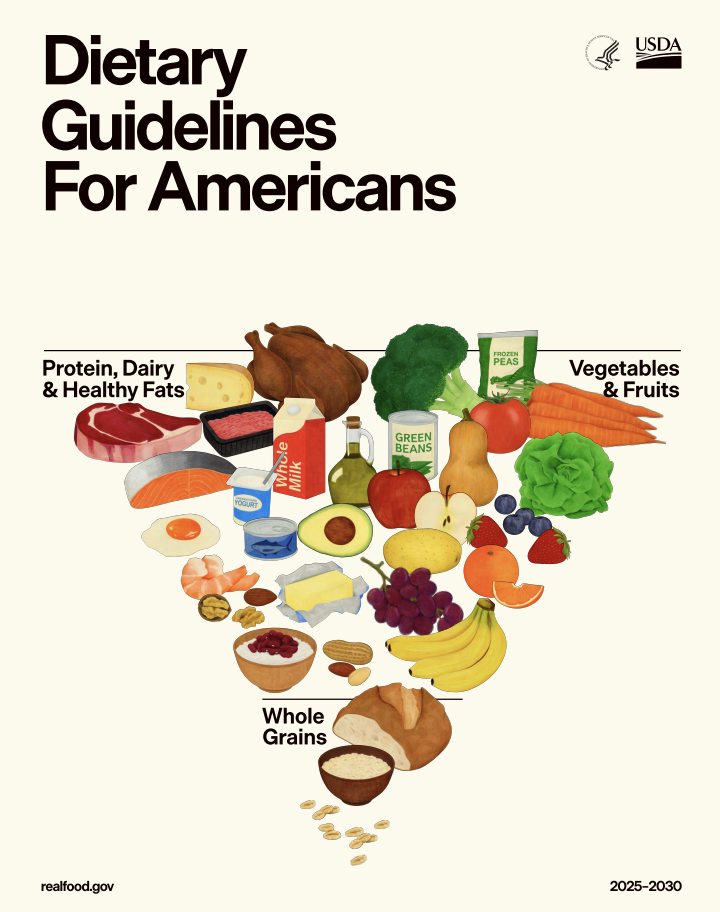

Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, meat, eggs, dairy, beans, nuts, and seeds once again form the foundation of a healthy diet. Highly processed foods, engineered combinations of refined starches, sugars, oils, and chemical additives are finally named as major drivers of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature decline.

To a medieval Benedictine abbess, this would not sound new at all.

Hildegard of Bingen taught more than nine centuries ago that food carries viriditas, a living, greening power that sustains the body and steadies the soul. When food is stripped, refined, or excessively manipulated, that vitality is lost. What remains may fill the stomach, but it does not truly nourish the person.

In Physica, Hildegard consistently distinguishes foods that are “full of strength” from those that are “empty” or “deadened” by excessive alteration. Modern nutrition science is now, belatedly, rediscovering this truth in biochemical language. In this sense, Hildegard would welcome the new food pyramid’s return to foods close to nature. She would recognize it as a long overdue correction after decades of treating food as isolated nutrients rather than as living substances. But she would not stop there.

While Hildegard affirmed the value of animal foods, she never promoted a diet dominated by them. Meat and dairy appear throughout her writings as strengthening and medicinal, yet also as potentially burdensome when consumed without measure.

In Causae et Curae, she warns that rich foods taken in excess “generate thick humors” and burden the organs, leading not only to bodily illness but to heaviness of mind and spirit. Meat, she teaches, strengthens the blood and flesh, yet when eaten too much and too often, it disturbs the balance of the body.

Dairy, too, must be approached with discernment. Hildegard praises milk and cheese for their nourishing qualities, especially for the weak or convalescent, but she cautions that excessive dairy creates internal congestion and dullness. In her medical worldview, such congestion does not remain confined to the gut; it spreads, affecting mood, clarity, and resilience.

Here the modern reader must pause.

The new American food pyramid corrects the error of demonizing animal foods, but Hildegard would caution strongly against swinging to the opposite extreme. Strengthening foods are not meant to dominate the diet. They are meant to support it.

Hildegard understood something our culture repeatedly forgets: true vitality is not created by piling on richness, protein, or density. It arises from balance and bio-individual needs. Foods that strengthen without burdening, nourish without dulling, and sustain energy without overwhelming digestion.

This is where the modern guidelines, for all their scientific rigor, remain incomplete.

They tell us what foods are associated with lower disease risk, but they do not ask whether those foods preserve lightness, clarity, and order within the human person. They speak in terms of prevention, not formation. Risk reduction, not harmony.

Hildegard’s approach was fundamentally different. She evaluated food by the order it created within the body and soul. In Physica, she repeatedly links improper eating not only to physical illness but to sadness, irritability, and mental confusion. Food, for her, shaped temperament and spiritual disposition as surely as it shaped flesh.

She would also notice what modern nutrition omits almost entirely: how one eats.

Meal during Hildegard Retreat

Hildegard warned against hurried eating, eating in sorrow or anger, and eating to excess during fatigue. In Causae et Curae, she notes that food taken when the body is already depleted or emotionally disturbed “turns against the person” rather than healing them. Digestion, in her understanding, was never merely mechanical. It was relational, emotional, and spiritual. Most strikingly, Hildegard framed appetite itself as a moral and spiritual reality. Disordered eating was not, in her view, primarily a failure of discipline. It was a distortion of desire. When virtue weakens, appetite becomes confused; when virtue is restored, appetite naturally moderates.

Temperance, for Hildegard, was not restriction but freedom. It allowed a person to receive nourishment without compulsion and strength without excess.

The new food pyramid, for all its progress, still lacks this dimension. It tells us what to eat, but not how to live. And yet, something hopeful is unfolding.

Modern science is finally affirming what ancient wisdom never forgot: that real food heals, that excessive processing harms, and that chronic disease is not an inevitable consequence of aging but a sign of profound dietary disorder. The language is different, the evidence newly quantified, but the direction is unmistakable.

Hildegard would not reject the new dietary guidelines. She would bless their return to reality and then gently insist that we go further. Because true nourishment is not found at the bottom of a pyramid.

It is found in balance, rhythm, virtue, and reverence for the living body entrusted to us.

Last minute sign up for HARMONY

Attend next Hildegard Workshop